Book reference: Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces

Lecture references:

Why use threads?

There are at least two major reasons you should use threads. The first is parallelism. The task of transforming your standard single-threaded program into a program that does this sort of work on multiple CPUs is called parallelization, and using a thread per CPU to do this work is a natural and typical way to make programs run faster on modern hardware. The second reason is to avoid blocking program progress due to slow I/O, while one thread in your program waits, the CPU scheduler can switch to other threads, which are ready to run and do something useful. Threading enables overlap of I/O with other activities within a single program.

How to support synchronization?

- support atomicity

- support sleeping/waking interation (most often, one thread must wait for another to complete some action before it continues)

What we will do is ask the hardware for a few useful instructions upon which we can build a general set of what we call synchronization primitives. By using this hardware support, in combination with some help from the operating system, we will be able to build multi-threaded code that accesses critical sections in a synchronized and controlled manner.

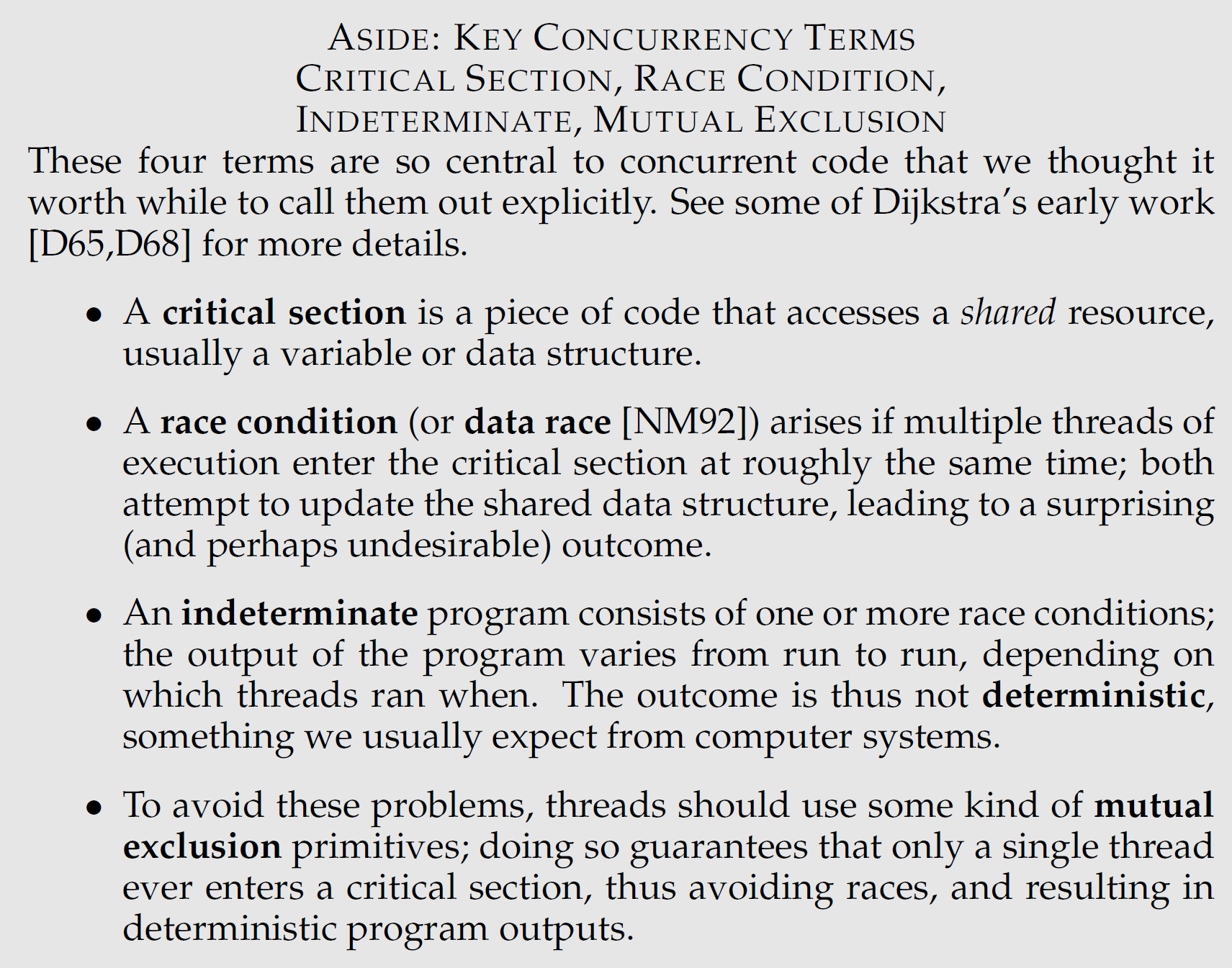

Terms:

Lecuture 7 Signals

A signal is a way to notify a process that an event has occured.

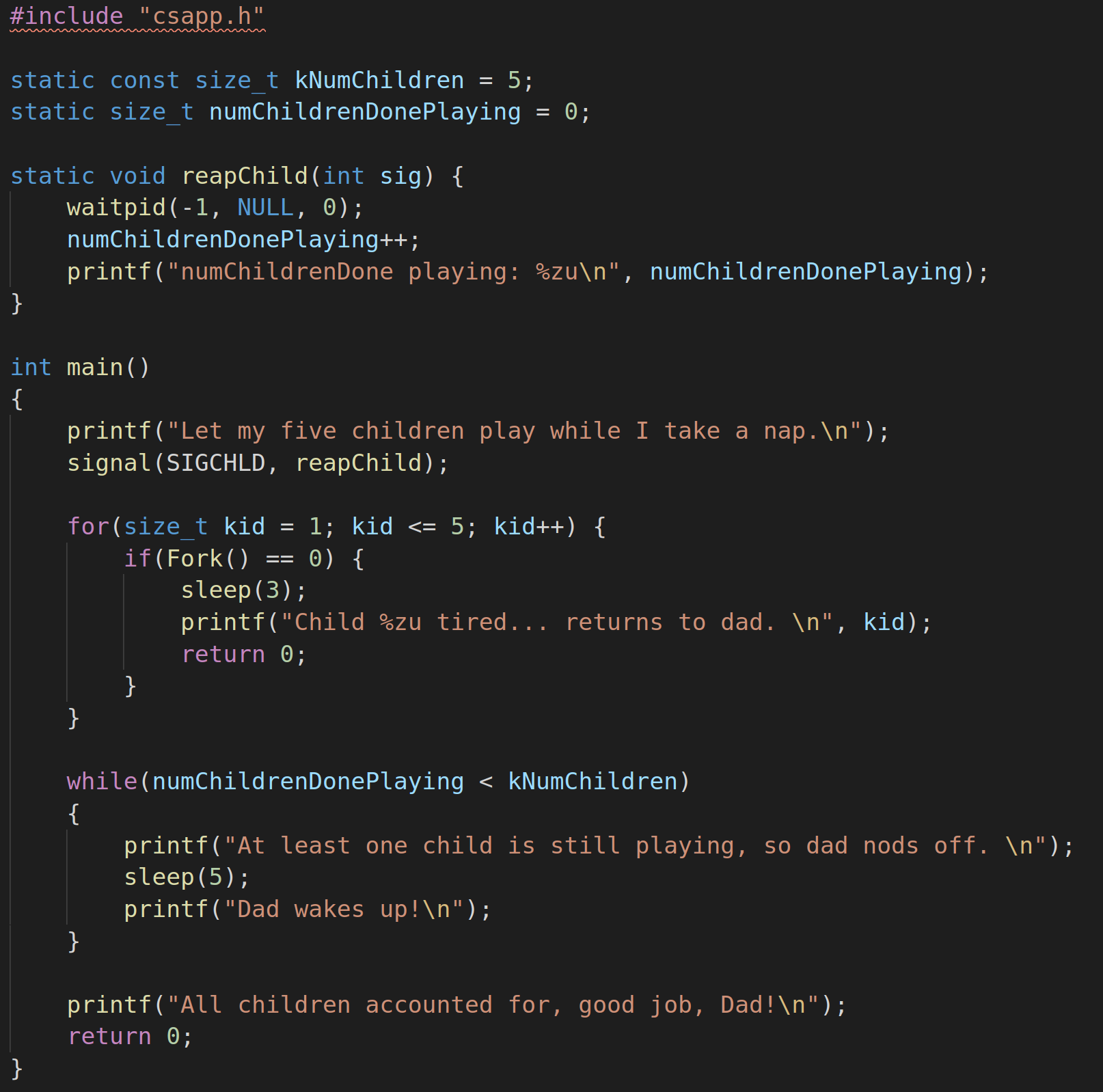

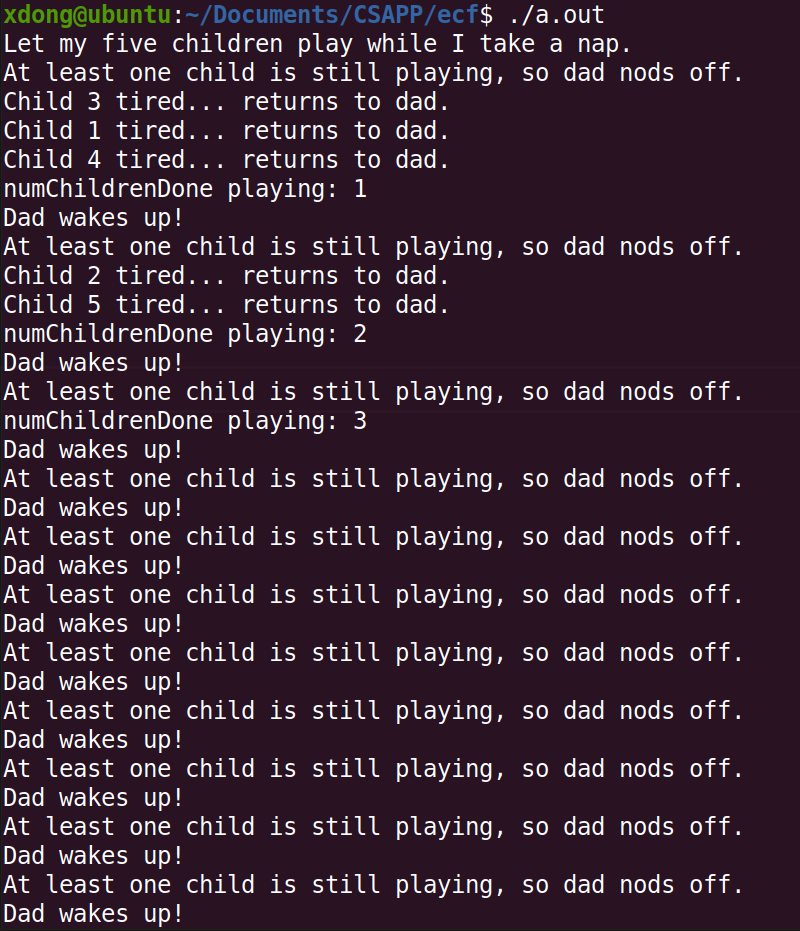

five-children example:

Problem with this program: it never stops.

It turns out that if children end in roughly the same time, there would be a kernel race condition. If a bunch of children end at the same time, the kernel would just say, fine, I am going to call one instance of the child handler function, you are going to deal with that result. The nice thing about it is that if you are already in the child, the signal handler and another child ends, it will call that signal handler again, so it’s not that you lost any children, it’s just that you have to deal with all the ones that have already ended immediately. So we’ll do it in the signal handler.

First step improvement:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

static void reapChild(int sig) {

while(true) {

waitpid(-1, NULL, 0);

numChildrenDonePlaying++;

printf("numChildrenDone playing: %zu\n", numChildrenDonePlaying);

}

}

Lecuture 8 Race conditions, deadlock and data integrity

The Race Condition Checklist

- Identify shared data that may be modified concurrently what global variables are used in both the main code and signal handler?

- Document and confirm an ordering of events that caused unexpected behavior what assumptions are made in the code that can be broken by certain orderings?

- Use concurrency directives to force expected orderings how can we use signal blokcing and atomic operations to force the correct ordering(s)?

Lecuture 11 Multithreading and Condition Variables

When coding with threads, you need to ensure that:

- there are no race conditions, even if they rarely cause problems, and

- there is zero threat of deadlock, lest a subset of threads are forever starving for processor time

mutexes are generally the solution to race conditions. We can use them to mark the boundaries of critical regions and limit the number of threads present within them to be at most one.

Deadlock can be programmatically prevented by implanting directives to limit the number of threads competing for a shared resource.

Lecuture 12 mutex, conditional_variable_any, semaphore

condition variable: a variable that can be shared across threads and used for one thread to notify another thread when something happens. A thread can also use this to wait until it is notified by another thread. We can call wait to sleep until another thread signals this condition variable. We can call notify_all to send a signal to waiting threads.

1. The general pattern of conditional_variable_any

cv.wait(m):

if there aren’t any permits, the thread is forced to sleep via cv.wait(m). The thread manager releases the lock on m just as it’s putting the thread to sleep.

Here’s what cv.wait does:

- it puts the caller to sleep and unlocks the given lock, all atomically (it sleeps, then unlocks)

- it wakes up when the cv is signaled

- upon waking up, it tries to acquire the given lock (and blocks until it’s able to do so)

- then, cv.wait returns

cv.nofity_all():

when cv is notified within grandPermission, the thread manager wakes the sleeping thread, but mandates it reacquire the lock on m, which is very much needed to properly reevaluate the permits == 0, before returning from cv.wait(m).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

static void waitForPermission(size_t& permits, condition_variable_any& cv, mutex& m) {

lock_guard<mutex> lg(m);

while(permits == 0)

cv.wait(m);

permits--;

}

static void grantPermission(size_t& permits, condition_variable_any& cv, mutex& m) {

lock_guard<mutex> lg(m);

permits++;

if(permits == 1)

cv.notify_all();

}

A second form of wait() is useful because the while loop is very common:

1

2

3

4

template <Predicate pred>

void condition_variable_any::wait(mutex& m, Pred pred) {

while(!pred()) wait(m);

}

The predicate is a function that returns true of false. We often use a lambda function for the predicate:

1

2

3

4

5

static void waitForPermission(size_t& permits, condition_variable_any& cv, mutex& m) {

lock_guard<mutex> lg(m);

cv.wait(m, [&permits]{ return permits > 0; }); //if true, re-acquire lock and unblocked; else keep waiting, release lock.

permits--;

}

Till now, the size_t permits, condition_variable_any, and mutex are collectively working together to track a resource count. They work to ensure that a thread blocked on zero permission slips goes to sleep indifinitely, and that it remains asleep until another thread returns one.

2. semaphore

A semaphore is a variable type that lets you manage a count of finite resources. It is a useful way to generalize the “permits” idea.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

constexpr on_thread_exit_t on_thread_exit {};

class semaphore {

public:

semaphore(int value = 0);

void wait();

void signal();

void signal(on_thread_exit_t ote);

private:

int value;

std::mutex m;

std::condition_variable_any cv;

semaphore(const semaphore& orig) = delete;

const semaphore& operator=(const semaphore& rhs) const = delete;

};

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

void semaphore::wait() {

lock_guard<mutex> lg(m);

cv.wait(m, [this] {return value > 0;});

value--;

}

/*

Why does the capture clause include the this keyword?

Because the anonymous predicate function passed to cv.wait is just that—a regular function.

Since functions aren't normally entitled to examine the private state of an object, the capture clause

includes this to effectively convert the bool-returning function into a bool-returning semaphore method.

*/

void semaphore::signal() {

lock_guard<mutex> lg(m);

value++;

if(value == 1)

cv.notify_all();

}

Using a semaphore is straightforward: you first declare a semaphore with a number of permits you would like:

1

semaphore permits(5);

When a thread wants to use a permit, it first waits for the permit, and then signals when it’s done using a permit:

1

2

3

permits.wait(); //if five other threads currently hold permits, this will block.

permits.signal(); //if other threads are waiting, a permit will be available.

Q1: what would a semaphore initialized with 0 mean?

A1: In this case, we don’t have any permits, permits.wait() always has to wait for a signal, and will never stop waiting until that signal is received.

1

semaphore permits(0);

Q2: What about a negative initializer for a semaphore?

A2: In this case, the semaphore would have to reach 1 before the wait would stop waiting. You might want to wait until a bunch of threads finished before a final thread is allowed to continue.

3. Thread rendezvous

Thread rendezvous is a generalization of thread::join. It allows one thread to stall - via semaphore::wait - until another thread calls semaphore::signal, often because the signaling thread just prepared some data that the waiting thread needs before it can continue.